Our learning pod will review chapter 10 from Richard Mayer’s “The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning,” titled The Redundancy Principle in Multimedia Learning, written by Slava Kalyuga and John Sweller. Our review will be presented under the following headings: What is the Redundancy Principle, Evidence Obtained Outside of Cognitive load Theory, Picture/Text Redundancy, Redundancy of Actual Equipment, Written/Spoken Text Redundancy, Second Language Learning, The Relation of the Redundancy Principle to other Cognitive Load Principles, and Instructional Implications of the Redundancy Principle. Through our analysis of the topics, we aim to provide an outline of why the redundancy principle is vital to the implementation of multimedia learning in teaching environments.

What is the Redundancy Principle?

Evidence Obtained Outside of Cognitive Load Theory

Picture/Text Redundancy

Chandler and Sweller (1991) were the first to discover the effect of picture/text redundancy during their research on the split-attention effect (SAE). The SAE “occurs when multiple sources of information that must be integrated to be intelligible are presented separately” (p. 251). In their findings, when the learner’s attention is ‘split’ between different modalities, such as pictures and text, their learning is reduced as their cognitive load increases. Although, in some cases, such as geometry, where images and text must be together to be intelligible, many examples of pictures and text in subsequent order are redundant. Chandler and Sweller (1991) described that the text almost always repeats the same information but in a different mode. This finding of picture/text redundancy is unintuitive because it is expected that everyone learns better with integrated diagrams and text, but in reality, as found through Chandler and Sweller (1991), separate diagrams and text, known as the split-attention, is superior to integrated material.

Redundancy of Actual Equipment

When people first learn to do something, they often believe that they are better off learning how to do it for themselves than if they were to read a manual. Chandler and Sweller (1996) hypothesized that using a computer and a computer manual to learn procedures could prove to be redundant, instead of just using the manual. Through their experiment, people who had learned with both the computer and the manual available were more likely to have an increased learning time and to perform poorly on subsequent practical tests using the computer program than those who only used the manual. By having both the manual and the computer, the cognitive load of the subjects may have been too high, therefore hindering their learning. A solution proposed for this was to have the instructions on the screen of the computer instead of using both the manual and the computer. Overall, they deduced that merely reading the manual with instructions and pictures alone was a more efficient way to learn how to use the computer program.

Written/Spoken Text Redundancy

When you examine multimedia materials, they are often composed of narrated text and written text, i.e. PowerPoint presentations. As established in the redundancy principle, an overlap of two modalities, such as written and spoken text, can inhibit learning because there is an increase of unnecessary and redundant information. Kalygua, Chandler and Sweller (1999) discovered that having identical written and spoken text interfered with learning and also that spoken text alone is more beneficial to learning than written and spoken text. Adding on, in an experiment done by Moreno and Mayer (2002a) found written text in a spoken/written scenario was disruptive to learning and redundant when based on spoken text only. Still, the opposite was not found redundant when compared to written text alone. In conclusion, the various experiment’s results indicate that presenting written and spoken text simultaneously is inefficient, harmful to learning, and redundant.

When you examine multimedia materials, they are often composed of narrated text and written text, i.e. PowerPoint presentations. As established in the redundancy principle, an overlap of two modalities, such as written and spoken text, can inhibit learning because there is an increase of unnecessary and redundant information. Kalygua, Chandler and Sweller (1999) discovered that having identical written and spoken text interfered with learning and also that spoken text alone is more beneficial to learning than written and spoken text. Adding on, in an experiment done by Moreno and Mayer (2002a) found written text in a spoken/written scenario was disruptive to learning and redundant when based on spoken text only. Still, the opposite was not found redundant when compared to written text alone. In conclusion, the various experiment’s results indicate that presenting written and spoken text simultaneously is inefficient, harmful to learning, and redundant.

Second Language Learning

Frequently while learning a new language, learners are given multiple modalities to learn with, including audio and visual. By practicing both simultaneously with foreign language learners, the cognitive load may present as extraneous (Diao, Chandler, and Sweller, 2007). When the cognitive load of learning a new language is too high due to using both audio and visual strategies, then the level of understanding the main ideas will be lower than a reading-only group. When a student has prior experience with listening to the new language, it has been shown that the student will still learn more efficiently by reading alone as opposed to reading and listening simultaneously (Ayres and Sweller, 2012). Overall, by using both written and spoken text simultaneously, the redundancy principle will come into effect, and the student will not have as efficient of a learning experience as they would with a reading-only form of instruction.

The Relation of the Redundancy Principle to other Cognitive Load Principles

The redundancy principle, which “applies to a situation when two or more sources of information can be understood separately without the need for their mental integration” (p. 257), also relates to two other cognitive load principles – split-attention and expertise-reversal. The split attention principle works in contrast in that it should be applied when separate sources of information must be processed together to be understood. For instance, the description of the operation of an electrical circuit would require reference to both a diagram and corresponding explanation, joined closely in space and time, to be adequately understood – doing so reduces the additional working memory resources required when mentally integrating multiple sources of information.

The expertise-reversal principle states that instructional methods that prove effective in aiding novices may negatively impact learners as levels of expertise increase. Supplementary material presented in multiple forms, such as integrated diagrams with written explanations or worked examples, may be essential and advantageous for the understanding of novices but become unnecessary and redundant for more knowledgeable learners with a more extensive network of existing schemas. As such, the redundancy and expertise-reversal principles are closely interconnected – a strong understanding of the redundancy principle, as well as the current knowledge level of your learners, is required to determine whether your instructional design could be considered redundant and thus result in the expertise-reversal effect.

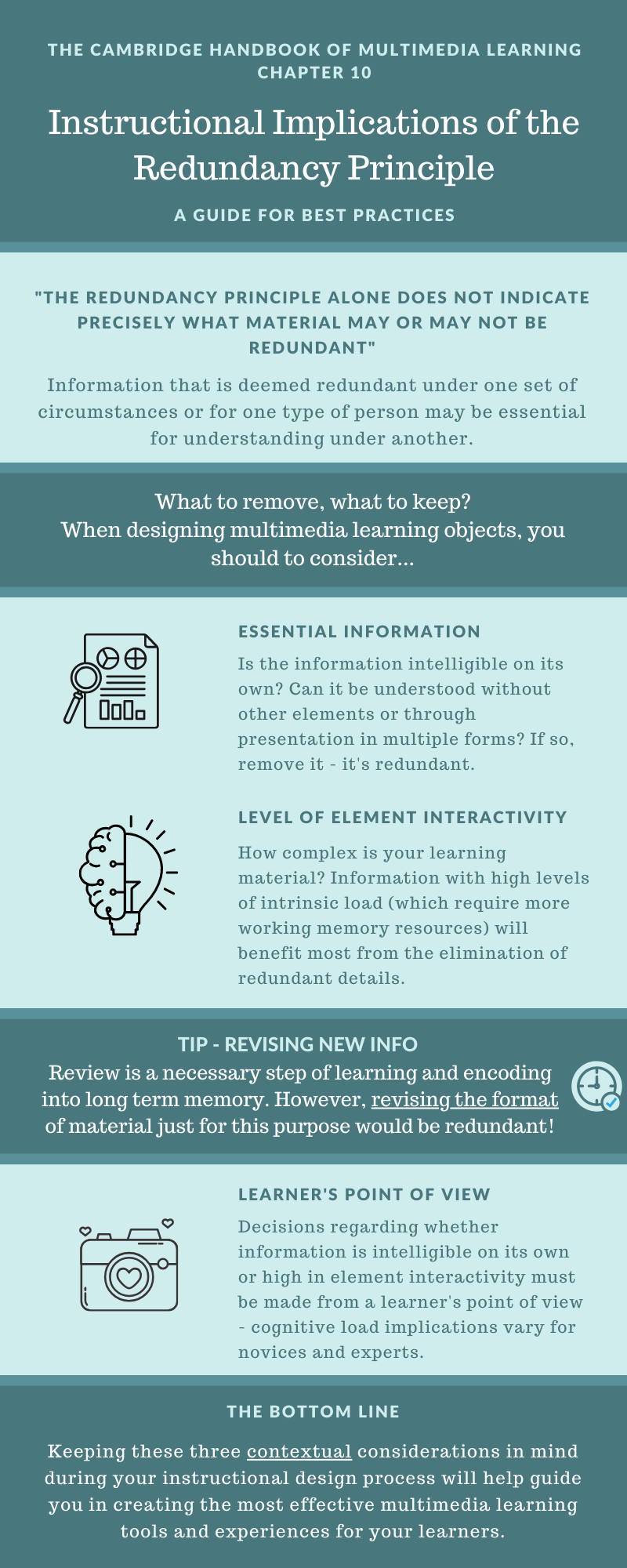

Instructional Implications of the Redundancy Principle

References

, & (1996). Cognitive load while learning to use a computer program. Applied Cognitive Psychology

Diao, Y., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (2007). The Effect of Written Text on Comprehension of Spoken English as a Foreign Language. The American Journal of Psychology, 120(2), 237-261. Retrieved June 21, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20445397

, , & (1999). Managing split-attention and redundancy in multimedia instruction. Applied Cognitive Psychology

Mayer, R. (2014). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 1-24). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI:10.1017/CBO9781139547369.002

, & (2002a). Learning science in virtual reality multimedia environments: Role of methods and media. Journal of Educational Psychology

Sweller, J. (2005). The Redundancy Principle in Multimedia Learning. In R. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 159-168). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511816819.011